And Just Like That...: How Bad Is Carrie Bradshaw's "Atrocious" Historical Romance Novel? The Experts Weigh In

Carrie Bradshaw knows good sex. But can she write good romantic fiction?

If you’ve been watching the latest series of And Just Like That…you’ll know that Carrie Bradshaw (Sarah Jessica Parker), as well as kidding herself that her on-off relationship with walking ick of a boyfriend Aiden Shaw (John Corbett) is going to work, has also been toiling away on a little literary sideline.

“I’m trying something new,” she tells her agent in episode three. “But it’s not a memoir, it’s fiction.” It’s not romantasy, as the agent excitedly asks, but it is a romance novel. There’s more! It’s a historical romance novel, decided on a whim in Carrie’s back yard in episode two, shortly before a colony of rats – fittingly for the 1846 setting – rushes at her feet.

And thus, Carrie’s newest work of art is born. The writer famously made a name for herself by writing a column entitled Sex And The City, and then, throughout the next six series of SATC; two films and then the Samantha Jones-less sequel, And Just Like That… we’re told she’s written six books in total. Sex and the City, MEN-hattan, A Single Life, Love Letters, I Do! Do I? and Loved and Lost, since you’re asking.

She’s clearly an accomplished writer – so much so French fans of her book famously recognised her on her sojourn to Paris in SATC season 6. So why shouldn’t the celebrated author branch out into historical fiction writing?

From episode two onwards, Carrie begins to share some snippets of her novel. And we know they must be good, as Duncan Reeves (Jonathan Cake), her esteemed, pipe-smoking British author neighbour, is in rhapsodies over the first chapter or two she gives him for feedback. “It’s brilliant,” he says. “The opening sentence! It just stopped me dead in my tracks…The way it flows is so propulsive.” Donna Tartt: watch your back.

But then, we get to see the actual writing.

The opening sentence throws us into the story:

“The woman wondered what she had gotten herself into.”

“Sitting in the sunlight, she felt the fog of the last few nights lift. She realised her tossing and turning and insecurities were remnants of another time. A time when she was less sure of her path. This is a new house, she reminded herself. A new life. This wasn’t her past…It was the present. May, 1846.”

Then, further excerpts describe in minute detail what she is wearing, but not her name, or the merest hint of actual plot:

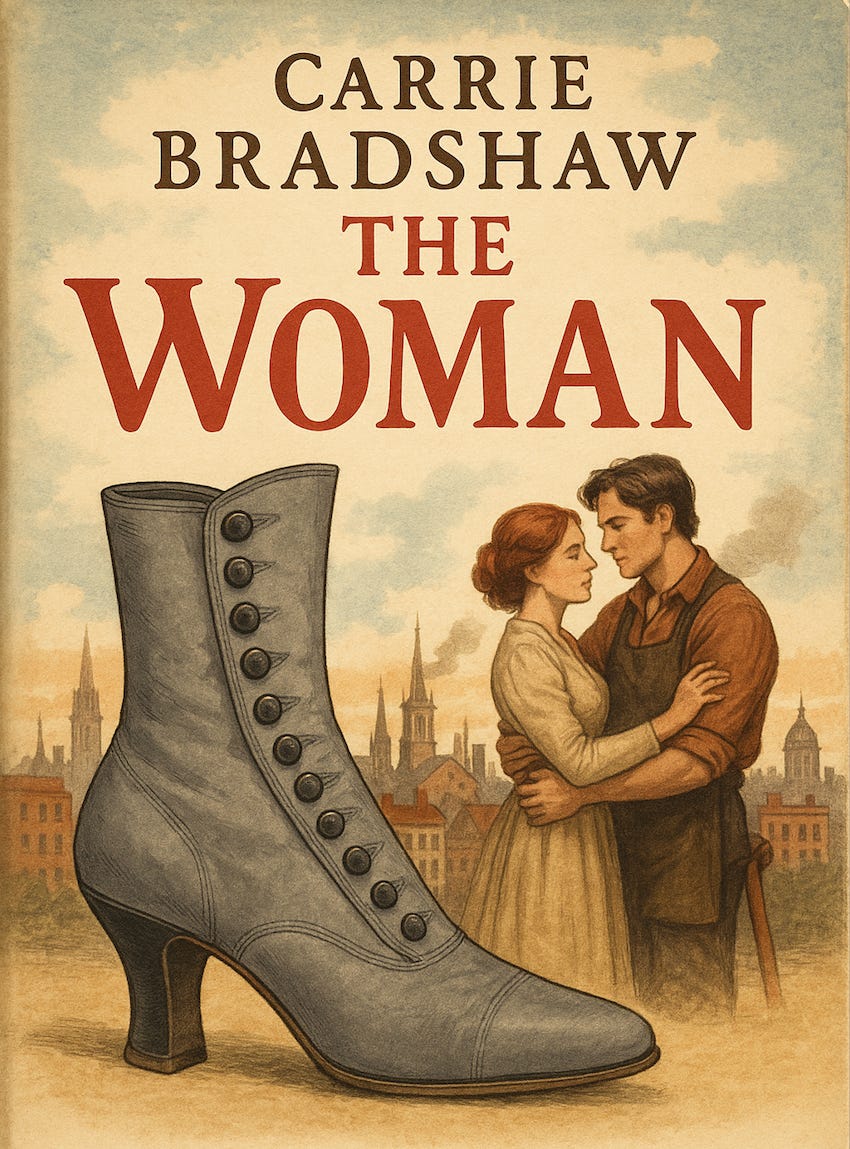

“The woman lifted her petticoat and hurried up the twisting iron staircase. She stepped carefully in her dove-grey buttoned boots to make sure she wouldn’t stumble. As she crossed the threshold and went on her way.”

“The woman threw open her windows to let the city in. She could hear the horses coming and going with their carriages, each one bringing an exciting possibility. The unexpected cool breeze on this hot afternoon reminded her that each day need not be an echo of the one before. There are endless adventures to be taken, if she simply dared to decide to take them. Putting one foot in front of the other, she stepped off the expected path and vowed to go wherever a day might take her.”

Her agent seems to be incredibly excited about this, as does Duncan. Social media, meanwhile, has been characteristically savage; calling it “atrocious”, “painful” and“awful”.

But how would three real experts working in literature and publishing critique the extracts from Carrie’s debut novel?

“I’m not sure why her neighbour is so enthusiastic about it,” says Meiko O'Halloran, senior lecturer in Romantic Literature at Newcastle University. “Perhaps his view that it is ‘brilliant’ tells us more about the questionable quality of his own writing. The opening sentence is especially banal!”

O'Halloran says that she can see influences of traditional romance novels in Carrie’s writing like Samuel Richardson’s Pamela or Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey or Emma. However, she points out: “These novels tend to have a strongly characterised heroine at the centre and readers are drawn into their story and experiences, whereas Carrie’s vague ‘Woman’ seems to be a bit of blank canvas.

“The fact it’s set in the specific year of 1846 gestures to the period when the Brontë sisters’ novels were being published. But their opening lines and female characters are a lot more interesting! Carrie could learn from Anne Brontë, for example, who draws readers into The Tenant of Wildfell Hall from the start with: ‘You must go back with me to the autumn of 1827.’”

“On the whole,” she says, “the writing is quite clunky. Carrie seems to be trying too hard by telling readers in a heavy-handed way that something interesting and momentous is happening, rather than letting them infer that. But novel-writing is new for Carrie, so it’s understandable that she needs to experiment to find her voice as a writer of historical romance.”

And despite Carrie donning a giant Bronte-like bonnet at the beginning of the series, staggeringly, this cos-play isn’t enough to make her an expert in this bygone era. “I question whether she’s done any historical research at all,” says Charlotte Cray, a freelance fiction editor, and former publishing director at Penguin Random House.

Reader, she has not. “My first note to her, as an editor, would be to ask her to read some letters and diaries from the time to get into her 1840s writers – Edgar Allan Poe, James Fenimore Cooper, Charles Dickens – and really submerge herself in the period. This is why so many historical fiction writers have an academic background or an intense devotion to their period.”

She adds of Carrie’s confused intro: “If I read the first sentence of a historical fiction submission and it sounded so casual and modern, I might expect to see some time travel in the plot to explain this modern register of free, indirect speech. Similarly, when Carrie uses the word 'insecurities' – a word that didn't have meaning in the psychological sense until 1917 – I'd assume a deliberate mixing of timeframes.”

“It reads, not unpleasantly, like something you might find on one of those battered train station bookshelves. You’d take a read while your phone is on 1% and you’ve run out of cigarettes and there’s a 45 minute wait for the next train to London.”

“I like it!” says Darren Biabowe Barnes, editorial director of CHEERIO Publishing. “It’s pretty good. It’s silly, yes, but I can see there being a market for it. It’s giving Danielle Steele or Jeffrey Archer. It reads, not unpleasantly, like something you might find on one of those battered train station bookshelves. You’d take a read while your phone is on 1% and you’ve run out of cigarettes and there’s a 45 minute wait for the next train to London.”

“It’s quite compellingly commercial,” he says, adding that Danielle Steele has sold more than a billion books in her career. “Fictional Carrie Bradshaw has ensured that every sentence actually does something, which is more than most writers, I’ll tell you that. Commercial fiction is not really about character, or description or scene or beauty of the language; it’s about story and moving the story forward and painting a picture and she does do that.

“That said, her use of deliberately arcane language is all deeply unserious. She repeatedly uses some quite cartoonish language to describe or to evoke the historicity of it all. But I definitely see a market for this.”

Cray agrees: “I think a commercial fiction imprint would go for Carrie's book and publish the novel as 'bookclub' fiction, using words such as 'sweeping' and 'transportive' in the copy and they'd put her name in very large type. You can see the cover with the starlight sky, turn of the century skyline and, goddamn it, the silhouette of a woman walking down a cobbled street. I can hear the cover brief in the art meeting.” AI, do your worst.

Whereas Carrie might be following in the footsteps of venerated authors like Cormac McCarthy (in The Road) or Daphne du Maurier (in Rebecca) by not naming her main protagonist, calling her simply: “The Woman”; however, the publishing experts are dubious about this choice.

“The idea that the main character is simply referred to as ‘the woman’ is quite trite,” adds Biabowe Barnes. “Generally you name your characters, and if you don’t, it’s deliberately a stylistic choice. I don’t know what purpose, if any, there is for Carrie not naming her character. Is it a statement?”

As series 3 of AJLT goes on, the penny quickly drops: ‘The Woman’, is of course, Carrie. Just like the “Big’s moving to Paris!’ meme, based on Carrie’s propensity to turn any conversation to her toxic relationship; Carrie has, unsurprisingly, once again made it all about her. O'Halloran explains: “Carrie is clearly using the novel as a vehicle to explore her feelings, and perhaps the earlier historical setting offers her some creative freedom to do that.”

And for that, perhaps she should be commended. Rather than chewing the ear off her friends about her terrible relationship with Aiden, she’s working it all out on the page, through the distanced lens of a dame trotting along the streets of NYC, 179 years earlier. “This could very much explain why she refers to the character as ‘The Woman’,” says Biabowe Barnes. “It’s clearly a cipher for herself, because it’s all a bit embarrassing otherwise.” Siphoning off your cringe behaviour to a lovelorn character’s inner monologue in a historical story? A perfect processing method for the delusionally-impaired; no notes.

“Maybe in this way Carrie is indeed doing something genre-defying and new.”

In fact, Carrie’s stumbled upon a new literary niche. As Cray points out: “Her writing seems to be in a self-help voice rather than a historical one. If she’s transported modern-day Carrie back in time instead of delving into her imagination and creating a viable character…I actually don't know any historical writers who write in this self-help memoir voice. It's quite unusual. Maybe in this way Carrie is indeed doing something genre-defying and new.”

And just like that, by being self-absorbed and stuck in the past; Carrie could end up as literature’s future. The woman smiled, a knowing smile, as she tapped her manicured, pink fingernails on her trusty slate-grey laptop. Every day was a new gift, she thought, just like turning the page of a best-selling historical romantic novel.

Carrie's column wasn't for Vogue; it was for a fictional paper, The Star. She did write some copy for Vogue in a later season.

It's Carrie's editor that she continually meets with, not her agent. We've never met her agent, if she even has one.